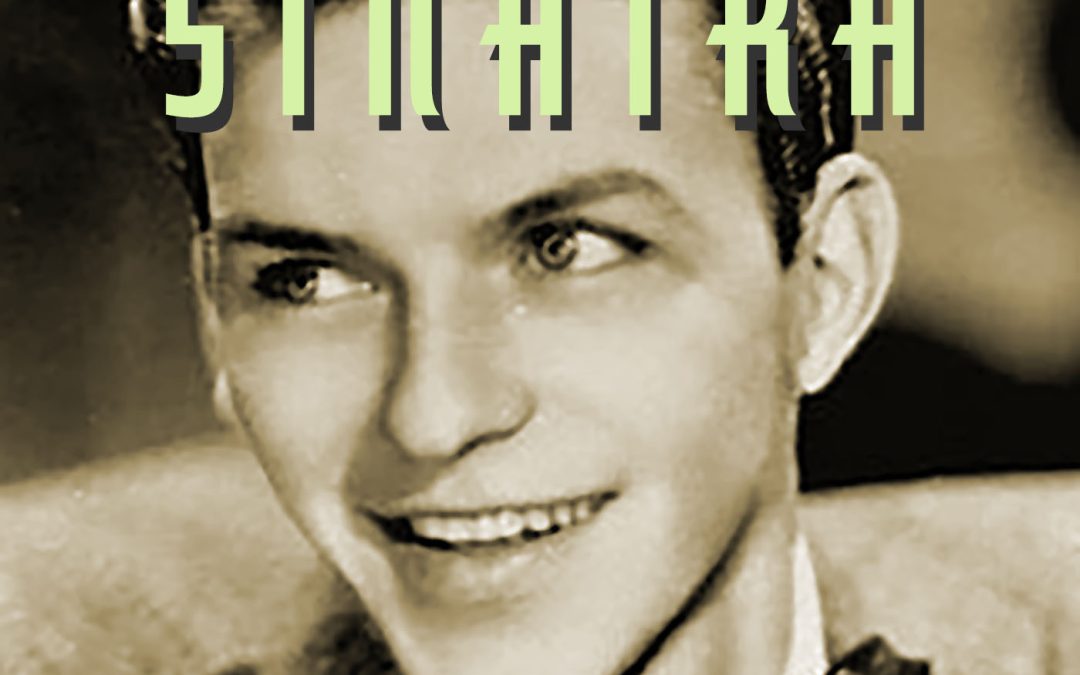

This episode of “The Secret History of Frisco” podcast introduces listeners to Jimmie Tarantino, a man described as a “louse, a blowhard, a barely literate, anti-Communist shake-down artist.” The episode delves into Tarantino’s early life in East Orange, New Jersey, and his eventual move to Hollywood where he became a peripheral member of Frank Sinatra’s inner circle, “The Varsity.”

I discuss Sinatra’s deep and complicated ties to organized crime and he used those connections to get out of his contract with bandleader Tommy Dorsey. It involved a pistol jammed in Dorsey’s mouth.

The podcast then details how Tarantino, with financial backing from Sinatra and mobster Mickey Cohen, started a tabloid called Hollywood Nite Life to extort celebrities. This venture eventually led to Tarantino double-crossing Sinatra, fleeing to San Francisco, and joining forces with crime boss Bones Remmer. The podcast also shares a moving story about Sinatra’s courage as a champion of civil rights and the remarkable life of boxing champion and war hero Barney Ross, who was also involved with Tarantino’s magazine.

TRANSCRIPT:

Welcome to the Secret History of Frisco Podcast. I’m your host, Knox Bronson. We have a wonderful episode for you today, part one the story to introduce you to Jimmie Tarantino. Who was Jimmie Tarantino?

I guess would depend on who you asked. He was well-connected man with powerful friends and the publisher of a gossip and scandal sheet called Hollywood NiteLife.

We will meet Frank Sinatra, Hollywood gangster Mickey Cohen, San Francisco Crime Boss Bones Remmer, boxing champ and war hero Barney Ross, and any number of other characters. Jimmie got around.

Jimmie was born in 1910 in Orange, New Jersey. Around the time the stock market crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, Jimmie had drifted into the world of professional boxing and organized crime, which, as we know, go together like home-grown tomatoes and fresh basil.

He began writing for a small boxing rag called The Knockout. At some point he crossed paths with Hank Sanicola, a boxer four years his junior, who later became a roadhouse pianist and then Frank Sinatra’s manager and partner in many ventures.

I can find no record of Jimmie and Frank himself crossing paths in either New Jersey or the Big Apple in the thirties, even though they lived only eleven miles apart when they were growing up, Jimmie in East Orange and Frank in Hoboken.

In the forties, Frank and Hank Sanicola had moved operations out to the West Coast and Jimmie trailed along after them, falling into Frank’s orbit, which I am sure was his intent. He ingratiated his way into becoming a member of “The Varsity,” a loose group of associates and hangers-on around Frank, pre-dating the infamous “Rat Pack” gang of the fifties and sixties.

[intermezzo]

We need to talk about Frank Sinatra’s connections to organized crime. Let’s just say they began shortly December 12, 1914, the day he was born, when his parents asked Willie Moretti, sometimes known as Willie Moore, to be Francis Albert Sinatra’s godfather. Willie was an underboss for the Genovese Crime Family. Moretti’s gang controlled the numbers rackets, horse racing, and gambling in Bergen County, New Jersey. He was a close associate of Frank Costello and spent time with Lucky Luciano at Mafia-favored resorts in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

When Frank was starting out, Willie helped him get bookings. In return, Frank kicked back a percentage. When Frank separated from his first wife, she complained to her cousin, a key member of Willie’s gang, of their difficulties. Willie got in touch with Frank and told him to move back home. Frank moved back home. By this time, Willie had financial interest in Frank’s showbiz career as well.

In late 1939, Frank joined Tommy Dorsey’s band. On January 26, 1940, Sinatra made his first public appearance with the band at the Coronado Theatre in Rockford, Illinois, opening the show with the song “Stardust”. Dorsey would later recall: “You could almost feel the excitement coming up out of the crowds when the kid stood up to sing. Remember, he was no matinée idol. He was just a skinny kid with big ears. I used to stand there so amazed I’d almost forget to take my own solos.”

They became close. Frank asked Tommy to be his daughter Nancy’s godfather. They made great music live and in the studio, making twenty hit records that first year. Frank’s star kept rising and by 1942 he was chafing under Dorsey’s contract, which not only limited his creative freedom, but took 43% of his lifetime, that’s right, 43% of his lifetime earnings.

There is famous quote about the music business, attributed to Hunter Thompson. It goes, “The music business is a a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.” While he didn’t actually say that, the good doctor was actually writing about television journalism in a column for the San Francisco Examiner in 1985, it’s easy to see why the musical mutation has embedded itself into the Zeitgeist for eternity. Why? Because it’s true!

Frank desperately wanted to go solo, not just for the money, he wanted to knock Bing Crosby, the biggest singer in the world, off his perch and he couldn’t do that as the singer in Tommy Dorsey’s, the headliner, Tommy Dorsey’s band. He put together a consortium and offered Tommy $60,000, approximately $1,200,000 today, to buy out his contract. Tommy refused. He knew Sinatra was the golden goose to end all golden geese.

Frustrated, Frank went to see his godfather, the Mob underboss Willie Moretti, and told him of his predicament.

Willie and and some muscle paid a visit to Tommy Dorsey’s home a few days later. Legend has it that Willie stuck a pistol into Dorsey’s mouth and told him he would kill him if he didn’t release Frank from the contract. I believe this to be true.

Tommy sold the contract for either $1 or a few thousand dollars, depending on which story one reads, and Frank Sinatra was a free man at last.

Sinatra immediately stole Alex Stordahl, Dorsey’s music director, away from Dorsey. Frank offered him $650 a month, five times what Dorsey was paying him, to come along with him as his personal arranger. Stordahl jumped shipped and became Frank’s long time musical collaborator, arranging many of his greatest hits. Dorsey and Sinatra never reconciled their differences.

Volumes have been written linking Frank Sinatra deeply to organized crime and the biggest bosses, Lucky Luciano, Sam Giancana, Willie Moretti, Mickey Cohen, and Frank Costello as mentioned before, and even Bones Remmer in San Francisco. They are not, at this point, germane to the Jimmie Tarantino’s story, although Jimmie went to work for Bones when he arrived in San Francisco after fleeing Hollywood and Frank’s wrath.

Frank Sinatra was a complex man. He had a legendary temper. He consorted with criminals and sometimes performed services for them, like smuggling cash into Cuba for Lucky Luciano. He clearly could be quite generous. He was known to be absolutely stand-up and loyal to his friends. Some consider him the greatest singer of the twentieth century. He believed the music he made came from another dimension. Most musicians know this, but I find it notable that he said it out loud, given his often loutish reputation. A complex man, indeed.

There is one other aspect to Frank Sinatra that remains in the forefront any time I think of him and that was his lifelong dedication to the Civil Rights movement and the battle against racism in all corners of our society. We will do a bonus episode about how the FBI watched him closely for many years for both his association with criminals and for his support of civil rights for black people.

In his FBI file, there is a story I’d like to share. I’m just going to read it verbatim. We will get into more detail at a future time. This is what the FBI wrote:

“A few months after World War II ended and just after the release of the movie, The House I Live In, Sinatra made headlines trying to diffuse racial tensions in Gary, Indiana, where white high school students were boycotting classes to protest a desegregation effort.

Confronting a rowdy and antagonistic audience in the school auditorium, Sinatra stood center stage, his arms folded, staring down the crowd for two anxious minutes until the catcalls and stomping gave way to absolute silence. Then he stepped up to the microphone and announced, Hoboken-style, “I can lick any son of a bitch in this joint. ”

Hostility gave way to cheers, but his impassioned plea for tolerance ended up insulting some locals and failed to end the strike. It also cemented the boyish singer’s status as a hero to American liberals of every stripe, including Communists.”

I love it. He travels to Gary, Indiana, at his own expense to try to cool things down in an emotional situation, that of an early effort to desegregate the schools and he gets up there and announces, “I can lick any son of a bitch in this joint. ”

You’ve got to love it, too. And Frank.

[intermezzo]

In 1940s Hollywood, Sinatra gathered around himself a group of men that came to be known as “The Varsity,” a precursor to his notorious Rat Pack of the Fifties and Sixties. It was, for the most part, a loose group.

Among them were a couple of songwriters and ex-boxer bodyguards, his arranger Alex Stordahl, his friend, partner, pianist, sometimes bodyguard and songwriting collaborator, Hank Sanicola. There were Manie Sacks, Nic Sevano, and Ben Barton, all involved in Sinatra’s music publishing businesses. Manie was Frank Sinatra Junior’s Godfather and reportedly was the one to turn off the unlit gas burners in one of Frank’s attempted suicides.

Last but not least in The Varsity line-up was Jimmie Tarantino, a small-time hustler who scraped by writing for The Knockout on a freelance basis. It’s hard to say what, if anything, Jimmie brought to The Varsity, but it was here he became privy to a lot of Hollywood gossip and had the idea for a shakedown rag called Hollywood Life. He changed the name to Hollywood Nite Life when he moved north to Frisco.

Jimmie saw an opportunity for a scandal sheet that published titillating gossip about Hollywood’s stars and other celebrities, while extorting others in order to keep their names out of the magazine.

Both Sinatra and LA’s top mobster Mickey Cohen invested in the fledgling publication. Soon, “Salesmen” for Hollywood Nite Life began extorting celebrities with secrets to hide, giving them the option of either buying an ad in the magazine or to become the subject of an exposé.

There is no question that Frank Sinatra and his friend, gangster Mickey Cohen, invested in Jimmie’s tattle sheet. Depending on who tells the story, the individuals. their motivations and involvement with Hollywood Life vary.

In the book, Frank Sinatra and the Mafia Murders, published by Ad Lib Publishers in 2022, authors Mike Rothmiller and Douglas Thompson wrote:

“Just about every spectacular girl in the world gravitated to Hollywood, hoping to get into pictures. Since only a small percentage succeeded, the town was ridiculously overstocked with ridiculously available young women, all of them working the angles, doing absolutely anything they could to get their moment under the Klieg lights. Sinatra couldn’t turn a corner without smacking into temptation. He made a $15,000 investment to keep many of such temptations private.

“With mobster Mickey Cohen he invested in Hollywood Nite Life a weekly gossip magazine run by a low life called Jimmy Tarantino. It was, discreetly, owned by Frank Costello, the boss of the New York Luciano ‘Family’.

“The scam was that stars were approached and advised to take paid advertisements out in the magazine, or their naughty or illegal behaviour would be a splash of headlines. It was a shakedown, blackmail and, in time, Tarantino would get done for extortion. In the moment, Sinatra received favourable reportage.

Frank himself, when testifying before The Kefauver Commission on organized crime in 1951, told a slightly different story.

In his private testimony to the Kefauver Committee, in 1951, Sinatra gave a different version of the story:

Senator Kefauver said, “We have information to the effect that you gave Tarantino quite a large sum of money to keep him from writing a quite uncomplimentary story about you.”

Frank replied, “Well, you know how it is in Hollywood…Jimmy called up and said he had an eyewitness account of a party that was supposed to have been held down in Las Vegas in which some broads had been raped or something like that. I told Jimmy that if he printed anything like that he would be in a lot of trouble.”

The next question was, “Did he ask you for money?”

Frank said, “Well, I asked Hank Sanicola, my manager, to handle it and that was the last I heard of it…”

Another question: Did Hank tell you he paid Tarantino?

Frank’s answer: “Well, I understand Tarantino was indicted and I don’t know the rest of the story, but the Hollywood Nite Life quit publishing this crap afterward.”

Let’s hear from the man himself. In the late Forties, Jimmie Tarantino went to the FBI to get his story on the record, fearing reprisals from San Francisco Examiner Editor Bill Wren, who ran San Francisco and was a sworn enemy of Jimmie and his boss, Bones Remmer.”

This is how the FBI reported Tarantino’s statements:

“Tarantino advised that the magazine, “Hollywood Nite Life,” was incorporated in California in 1945 by Barney Ross, former welterweight champion, Henry Sanicola and himself. He reported that Sanicola is a very good friend of Frank Sinatra and that Sinatra had helped finance the deal with $15,000. This group operated the magazine for approximately six months, after which time Tarantino said he acquired full ownership.

“On November 10, 1949, Inspector Frank J. Ahern, San Francisco Police Department, advised the Los Angeles FBI Office that he believed that Tarantino’s publication was sponsored by Frank Costello’s criminal syndicate and that Tarantino had been invaluable in infiltrating political machines in order to allow Costello’s mobsters to operate with the co-operation of such politicians and officials.

“Tarantino specializes in sensationalism and during 1949 featured a so-called “expose” of the narcotics traffic in Hollywood which allegedly involved Judy Garland, Actress, and Actor Robert Mitchum. He is reported to take orders from Michael “Mickey” Cohen, Los Angeles’ leading hoodlum, and was friendly with the late Bugsy Siegel. ”

So it’s kind of like peering into a quantum cloud, isn’t it? Depending on who is looking at it, the wave-form collapse into what we perceive as reality takes a slightly different form.

I can only find a couple references to Barney Ross in relation to Jimmie. Barney, born Dov-Ber Rosofsky to Jewish immigrant parents in 1909, was a wartime hero and national celebrity. One was in Frank Sinatra’s FBI file, the other was in an oral history of San Francisco politics and crime by Thomas C. Lynch, San Francisco District Attorney in the Forties and later becoming the State of California Attorney General. We will dive into that history in our next episode. It’s fascinating!

When Dov’s father was murdered in a holdup on Chicago’s West Side in 1923, he turned to boxing to earn money for his mother and five siblings. He was a champion, victorious in 77 of 81 bouts over the course of his career. After winning amateur bouts, Dov would pawn the awards—like watches—and set the money aside for his family. Apparently, Al Capone bought up tickets to his early fights, knowing some of that money would be funneled to Dov.

At some point, he changed his name to Barney Ross so as to not sully the family name with the boxing world’s close connection to organized crime.

In his last fight, Barney defended his title on May 31, 1938, against world champion Henry Armstrong, who beat him by a decision in 15 rounds. Although Armstrong pounded Ross mercilessly and his trainers begged him to let them stop the fight, Ross refused to stop or go down. Barney Ross had never been knocked out in his career and was determined to leave the ring on his feet. Some boxing experts view Ross’s performance against Armstrong as one of the most courageous in boxing history.

In 1942, he retired from boxing and enlisted in the Marine Corps to fight in World War II.

He served with B Company, 1st Battalion, 8th Marines during the Battle of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. One night, he and three other comrades were trapped under enemy fire. All four were wounded; Ross was the only one left able to fight. Ross gathered his comrades’ rifles and grenades and single-handedly fought nearly two dozen Japanese soldiers over an entire night, killing them all by morning.

Two of the Marines died, but he carried the third on his shoulders to safety; the other man weighed 230 lbs. compared to Ross’ 140 lbs. As I said, a hero.

Upon his return to the States, he developed an addiction to morphine during the treatment of the injuries he had suffered in that battle. Released from the hospital, he started using street heroin, sometime spending as much as $500 a day on it. He eventually entered treatment and kicked the habit.

Barney spent his last days using his celebrity status in promotional work for casinos and other businesses. For a while, he wrote a sports column for Hollywood Nite Life. Much later, when his old friend Jack Ruby, whom he knew from running the mean streets of Chicago as a teenager, went to trial for killing Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Barney appeared as a character witness.

Jimmie Tarantino’s stay in Hollywood didn’t last too long after the launch of the magazine. Within a year or so, legend has it that he got the goods on a salacious Sinatra story and shook his benefactor down for eight thousand dollars. Sinatra was furious and Jimmie had to leave town, fast, the before sundown kind of fast. He came north and went to work for Frisco’s gambling kingpin, Bones Remmer.

Again, there are numerous versions of these events, connections, as well as the individuals involved and their motivations, more details lost in the quantum foam.

Jimmie was no angel, nor were any of them. In my preview episode of this podcast, I told the story of meeting Shell Cooper in the mid-seventies when I worked at the San Francisco Examiner as an editorial assistant. Shell worked at the bar in the Pickwick Hotel across the street from the paper. Shell had been, like Jimmie Tarantino, one of Bones Remmer’s lieutenants. Shell asked me to find a picture in the Examiner archives and I found instead wiretap transcripts from 1950 of Bones, Jimmie, and Shell talking to each other. This opened up a whole new perspective of San Francisco history to me, which is what we are exploring here in the Secret History of Frisco.

Shell told me a number of stories about the era but he really didn’t want me to write about it. He said, “The ballgame’s over. People would get hurt. But I’ll tell you one thing, they were just as dirty as we were.”

And then he said it again, “They were just as dirty as we were.”

I’m going to assume he meant, by “they,” Bill Wren, the editor of the Examiner, columnist Freddie Francisco, District Attorney Thomas Lynch, and the rest.

I’ve never forgotten how adamantly he spoke those words.

Jimmie’s arrival in San Francisco sparked a whole new era in the Hollywood Nite Life story. I will talk more about the mischief he got into upon his pilgrimage to the cool grey city of love in the next episode of The Secret History of Frisco. Be sure to join us.

[intermezzo]

The Secret History of Frisco is ostensibly a listener supported podcast. Main episodes will always be free. Our website is www.thesecrethistoryoffrisco.com. Please join us on Patreon at www.Patreon.com/Frisco. Visit the website for the transcript and show notes. Please take advantage of our free membership option on Patreon. Paid tier members, starting at as little as $1 a month, will receive bonus episodes and other perks of membership.

If you enjoy the podcast, please tell your friends about it, especially those who enjoy San Francisco or true crime history. Word of mouth is the absolute best means of promotion for any creative endeavor in this world of algorithms and the ceaseless barrage of ads, notifications, and appeals on every digital platform. If you are aware of some particular aspect of San Francisco history in the thirties and forties you would like me to research, or a story to tell, please let me know.

Once again, I’m your host, Knox Bronson. Thank you for listening. Until next time, please get a little crazy and call it Frisco.

Jimmie Tarantino had two sons. One was named James. You did get some of the story correct. BTW – He was from Orange, NJ. Not East Orange. Same place I was born

Thank you for writing, John. I found a couple references, including the oral history of San Francisco DA (in the late 40s) Thomas Lynch, which identified your father as coming from East Orange.

I’m doing the best I can to be accurate. If you would like to set the record straight about your father, I’d be happy to have you on an episode of The Secret History of Frisco podcast. I have lots of questions, as well. Please email me at kn**@*********on.com. I hope to hear from you.

John- I have redone the ending of the first episode, removing my own editorializing about your father.

I added something Shell Cooper, an associate of your father’s whom I had the pleasure of meeting in the Seventies, once told me: “I don’t care what anyone says, they were just as dirty as we were.”

He left it at that.

Once again, I invite you to tell your father’s story however you would like on the podcast. Thanks again for writing.